Introduction

Eli Whitney’s name is etched into American history for his invention of the cotton gin, a device that transformed the Southern economy. But to stop there is to ignore one of his most revolutionary contributions—the mechanization and standardization of firearms production. In an era when weapons were handcrafted and parts unique to each piece, Whitney introduced a disruptive concept that forever altered the trajectory of military logistics and industrial manufacturing: interchangeable parts.

This article explores the true extent of Eli Whitney’s contribution to American firearms manufacturing, detailing how his vision and methods laid the groundwork for the mass production of weapons, catalyzed the American Industrial Revolution, and influenced the development of modern manufacturing systems across multiple industries.

Early Life and Mechanical Genius

Eli Whitney was born on December 8, 1765, in Westborough, Massachusetts, into a modest New England farming family. Demonstrating mechanical aptitude from a young age, he began manufacturing nails during the Revolutionary War to earn extra income and later constructed a violin entirely by hand. These early projects reflected a budding engineer's mind—practical, inventive, and relentless in pursuit of efficiency.

In 1789, Whitney entered Yale College, where he received a classical education but retained his mechanical focus. Graduating in 1792, he originally planned to study law. However, a post-graduation tutoring opportunity in Georgia introduced him to the South’s cotton economy and ultimately led to his development of the cotton gin in 1793. While the gin brought him widespread fame, it was another invention—less dramatic in name but more impactful in scope—that would define his lasting contribution to American industry.

The 1798 Musket Contract and a Nation’s Need

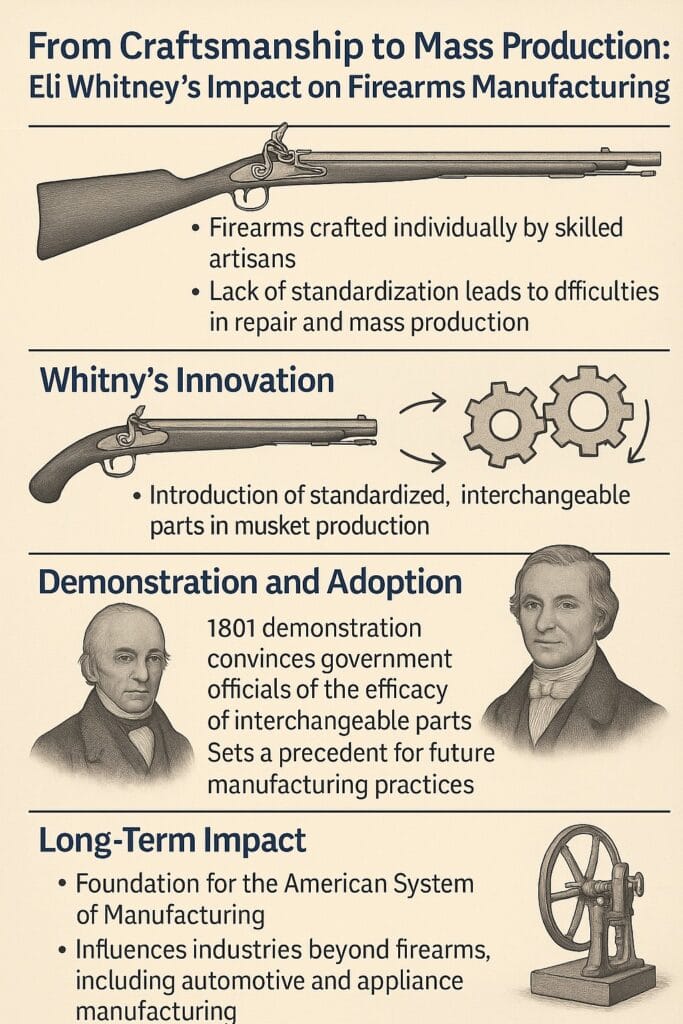

By the late 1790s, the United States found itself on uncertain footing amid escalating tensions with France during the Quasi-War. Fearing open conflict, the federal government began fortifying its military capacity, particularly in the production of small arms. At that time, most firearms were produced by master gunsmiths in small quantities. Each weapon was a bespoke creation; no two locks, stocks, or barrels were exactly alike.

In 1798, Eli Whitney secured a government contract to produce 10,000 muskets over a two-year period—an enormous order by the standards of the day. While Whitney had no prior experience manufacturing firearms, he offered something unprecedented: a vision of mechanized production using standardized components. His proposal did not simply meet a wartime need—it proposed an entirely new method of manufacturing.

The Revolution of Interchangeable Parts

Prior to Whitney’s work, repairing a damaged musket often required replacing or modifying parts by hand, sometimes necessitating the services of a skilled gunsmith in the field. The inefficiencies were glaring: logistical delays, high costs, and inconsistent performance.

Whitney theorized that if gun parts could be made to exact specifications, they could be mass-produced using unskilled or semi-skilled labor and easily assembled or repaired. This concept of interchangeable parts had been discussed in Europe—particularly by French military engineer Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval—but it had never been implemented on a meaningful industrial scale.

Whitney established a factory in East Haven, Connecticut, outfitted with a water-powered trip hammer and a series of lathes and boring machines. He applied rigorous measurement systems to produce standardized parts for barrels, stocks, locks, and triggers. Though it would take years of refinement, Whitney’s factory moved from an artisanal model of production to a mechanized system.

Debunking the Myths and Assessing Performance

Although it is often claimed that Whitney immediately delivered fully interchangeable muskets, the reality was more complex. His initial deliveries were delayed—far beyond the two-year contract term—and many of the early firearms still required hand-fitting. Yet Whitney’s genius was not in perfection, but in vision. He demonstrated in a famous 1801 presentation to Congress (or more likely to government officials such as President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson) that he could assemble muskets from randomly selected parts, underscoring the practicality of his method.

While modern historians debate whether these demonstrations were theatrics or legitimate proofs-of-concept, the broader industrial impact is undeniable. Whitney’s muskets, typically modeled after the French Charleville .69 caliber smoothbore design, became the forerunners of standardized American infantry arms. By the War of 1812, his factory and others influenced by his methods had begun to supply consistent, interchangeable firearms to U.S. troops.

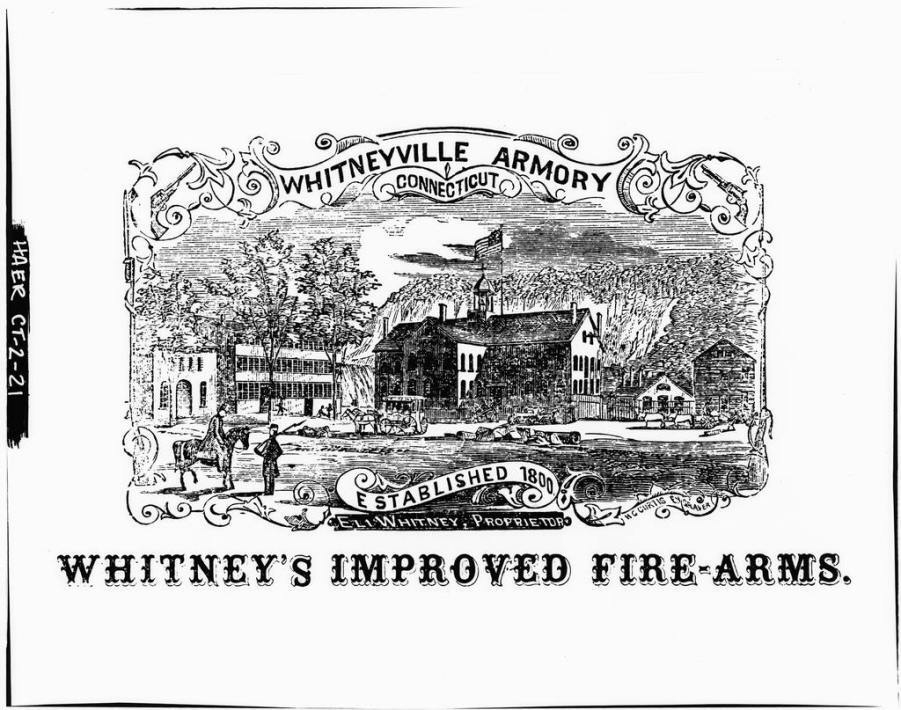

Whitneyville Armory: An Industrial Template

To fulfill his federal contract, Whitney built what would become known as the Whitneyville Armory on the Mill River in Hamden, Connecticut. Though it began with modest equipment, it gradually evolved into one of the earliest examples of an integrated manufacturing facility. Whitney adapted machine tools to specific tasks, such as milling lock plates or boring barrels, and implemented workflows that allowed relatively unskilled labor to perform specialized functions.

His armory became a prototype for later U.S. armories at Springfield and Harpers Ferry, which adopted and expanded on Whitney’s techniques. These federal armories eventually trained generations of machinists and engineers who would disseminate the doctrine of precision manufacturing throughout the United States.

Influence on American Industry and the American System

By pioneering interchangeable parts and semi-automated manufacturing, Whitney became one of the foundational figures of what economic historians later termed the “American System” of manufacturing—a production model characterized by:

- Mechanized production using specialized tools

- Division of labor

- Standardized parts allowing mass assembly

- High-output capacity from unskilled labor

These principles would later define American industrial superiority, influencing manufacturers such as Samuel Colt, who mass-produced revolvers, and Oliver Winchester, whose lever-action rifles became an American icon.

Beyond firearms, Whitney’s influence extended to industries such as clockmaking, sewing machines, agricultural equipment, and eventually, automobiles. The Ford Motor Company’s assembly line, often considered the pinnacle of industrial efficiency, would be inconceivable without Whitney’s foundational insights.

A Lasting Legacy: Beyond the Cotton Gin

Though he never produced fully interchangeable arms during his lifetime, Whitney's enduring contribution was the concept, refinement, and evangelization of standardized production. He died on January 8, 1825, after battling prostate cancer, but his legacy endured through his son, Eli Whitney Jr., who continued running the Whitney Armory well into the mid-19th century.

The principles Whitney championed were adopted by the U.S. Ordnance Department, which began enforcing interchangeability standards across contractors. By the 1840s and 1850s, thanks in part to continued government investment and innovators like Simeon North and John Hall, interchangeable firearms became a reality.

Conclusion: Eli Whitney and the Shape of Modern Industry

Eli Whitney’s legacy extends far beyond cotton or muskets. He introduced a framework for thinking about manufacturing not as an artisanal craft but as a replicable, scalable process. His vision transformed firearms from one-of-a-kind tools into standardized military assets, enabling faster repairs, easier logistics, and improved combat readiness.

Whitney’s conceptual leap was foundational to the Industrial Revolution in the United States. His influence bridged agriculture, defense, and heavy industry. Every engine block, rifle receiver, or microchip that rolls off a production line today owes something to Whitney’s realization that interchangeable parts were the key to mass production. You may also be interested in our coverage of Montrose March 14 Live Firearms Auction Preview.

To understand American industrial power—and the rise of modern armaments—one must understand Eli Whitney. His work redefined the relationship between labor, machinery, and output. He didn't just change how weapons were made—he changed how everything would be made. And that is the mark of a true revolutionary.

Eli Whitney: A Chronological Journey of Innovation

1765 – Birth and Early Inclinations

- December 8: Eli Whitney is born in Westborough, Massachusetts.

- Demonstrates mechanical aptitude early on, crafting nails and a homemade violin during his youth.

1789–1792 – Academic Pursuits

- Enrolls at Yale College in 1789, focusing on science and engineering.

- Graduates in 1792, initially intending to study law.

1793 – Invention of the Cotton Gin

- While residing in Georgia, invents the cotton gin, revolutionizing cotton processing by efficiently separating seeds from fiber.Encyclopedia Britannica

1798 – Government Musket Contract

- Secures a contract with the U.S. government to produce 10,000 muskets, marking a significant shift towards standardized manufacturing.

1801 – Demonstration of Interchangeable Parts

- Presents a demonstration in Washington, D.C., showcasing the assembly of muskets from interchangeable parts, impressing government officials and validating his manufacturing approach.

1817 – Personal Milestones

- Marries Henrietta Edwards, granddaughter of theologian Jonathan Edwards.

- Continues to refine manufacturing processes and expand his armory operations.

1825 – Passing and Legacy

- January 8: Eli Whitney passes away in New Haven, Connecticut, leaving behind a transformative legacy in manufacturing and industrial engineering.

If you know of any forums or sites that should be referenced on this listing, please let us know here.