Introduction

Among the multitude of breech-loading carbines issued during the American Civil War, few represent the intersection of innovation, field utility, and industrial complexity like the Smith Carbine. Though eventually overshadowed by repeaters like the Spencer and by the simplicity of the Sharps, the Smith Carbine earned its reputation through inventive engineering and broad deployment. Between 1861 and 1865, over 30,000 units were issued to Union cavalry forces, and its unique India-rubber and foil cartridge systems reflected a transitional era in firearms evolution. This article delivers an authoritative account of the Smith Carbine—from its inception and engineering to battlefield use, postwar surplus, and its legacy in blackpowder shooting today.

Gilbert Smith: The Inventor Behind the Weapon

Gilbert Smith of Buttermilk Falls, New York (modern-day Highland Falls), was an inventive gunsmith seeking to resolve a central limitation of early breechloaders: gas leakage at the chamber joint. Starting in 1855, Smith filed a series of patents aimed at solving this problem. His breakthrough arrived with U.S. Patent No. 17,644 (granted June 23, 1857), which introduced the break-action Smith carbine and a novel self-sealing cartridge. A follow-up, U.S. Patent No. 17,702 (July 11, 1857), detailed the rubber cartridge's flexible construction, designed to expand under pressure and seal the breech upon firing.

Smith's cartridges were constructed from vulcanized India-rubber, a material still relatively new at the time. This invention was not merely for convenience; it addressed the dangerous blowback common to poorly sealed breech mechanisms. Smith's concept was, in essence, one of the earliest instances of what modern shooters would call obturation: the sealing of high-pressure gases behind a projectile.

From Prototype to Procurement: Manufacturing Challenges

Though Smith was a capable inventor, he lacked the resources and infrastructure for mass production. In 1859, he licensed his design to two Baltimore entrepreneurs, Thomas Poultney and David B. Trimble. The firm of Poultney & Trimble became the primary contractor for the U.S. Government, though it relied on outside manufacturers for actual production.

Massachusetts Arms Company

Founded in 1850 and based in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Arms Company was an established maker of handguns and rifles. It received the initial Smith Carbine production contract. However, a catastrophic fire destroyed the factory in January 1861, delaying fulfillment. Despite the setback, they eventually delivered approximately 12,000 Smith carbines after reconstruction was completed.

American Machine Works

To cover the shortfall caused by the fire, American Machine Works of Springfield, Massachusetts, stepped in. Originally a supplier of industrial castings and machinery, the company pivoted to firearm production. By late 1863, it had received contracts to produce an additional 12,000 Smith carbines and was responsible for manufacturing a large portion of the total wartime output.

All carbines bore three stamps: “SMITH’S PATENT” (the inventor), “POULTNEY & TRIMBLE” (the contracting firm), and the manufacturing company (either “MASS ARMS CO” or “AM’N M’CH WKS”). Each firm maintained its own serial number series, explaining overlapping serials across specimens.

Mechanical Design and Operation

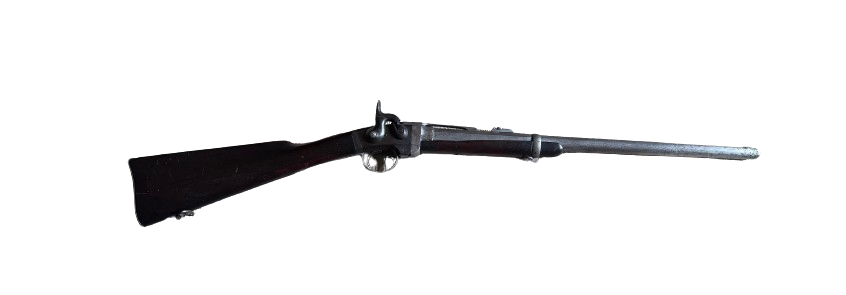

The Smith Carbine was a .50 to .52 caliber, single-shot, percussion-ignition, break-action firearm. The action opened via a spring-loaded button forward of the trigger guard. When pressed, the barrel would hinge downward roughly 90 degrees, exposing the breech.

- Overall Length: 39.5 inches

- Barrel Length: 21.625 inches

- Weight: 7.5 lbs

- Rifling: 1:62 twist with three shallow grooves

- Sights: Fixed front blade and flip-up rear leaf

Unlike the Burnside, which required both hands to open the action, the Smith could be operated one-handed—a critical advantage for cavalrymen managing reins. Its sturdy locking mechanism included interlocking conical surfaces between barrel and receiver, ensuring durability.

Cartridge Evolution: India-Rubber to Foil

India-Rubber Cartridges

The original Smith cartridge used a flexible vulcanized rubber case sealed with a paper or leather base. Upon ignition, the case expanded laterally, sealing the chamber and eliminating gas escape. Once pressure subsided, the cartridge contracted, allowing easy extraction.

Despite their innovation, these cartridges had field issues:

- Powder leakage from the flash hole during transport

- Flash hole erosion after repeated use

- Tendency to become brittle in cold weather

The Ordnance Department ordered millions of the distinctive rubber Smith cartridges from several contractors during the war, primarily from W.J. Syms & Brothers and Schuyler, Hartley & Graham. Surviving ordnance reports suggest total production ran to nearly four million rounds, making it one of the more substantial carbine ammunition programs of the conflict.

The Crispin Foil Cartridge

To address the rubber cartridge’s limitations, Ordnance Inspector Silas Crispin designed a foil-and-paper variant. Patented in December 1863 (U.S. Patents 40,978 and 40,988), these cartridges used thin brass foil sandwiched between two layers of heavy cartridge paper, with a waxed paper disk at the base to protect the powder from spillage.

Crispin’s cartridges were cheaper, easier to produce, and more resistant to environmental degradation. The later Poultney patent foil-and-paper cartridges (often associated with the Crispin patent) were purchased in huge numbers – about 8 million across all compatible arms – but a large portion remained in storage after the war. Only a fraction ever saw field issue in Smith carbines. They were also the precursor to metallic cartridges, with some experimental models incorporating primers for use in modified Smith carbines, though these never saw full deployment.

Combat Use and Cavalry Deployment

The Smith Carbine was issued to numerous Union cavalry regiments including:

- 1st Massachusetts Cavalry

- 6th and 7th Ohio Cavalry

- 3rd West Virginia Cavalry

- 7th Illinois Cavalry

It saw action in campaigns across the Eastern and Western Theaters. While field reports varied, many officers praised its accuracy and rate of fire. Rear Admiral David D. Porter reportedly favored it over the Spencer in naval trials, though that claim remains anecdotal.

Critics such as Major Raleigh Colston of the Virginia Military Institute noted that the action fouled quickly with residue, and soldiers could not fire without cartridges, creating logistical dependency. Nonetheless, the Board of Ordnance in 1860 ranked it highly, even recommending it over other tested designs.

Standardization and the Rise of the Spencer

In 1863, Brigadier General James H. Wilson led a comprehensive evaluation of cavalry arms, recommending .52 caliber as the new standard. Though the Smith was praised, the Spencer repeating rifle’s volume of fire made it the preferred choice for new contracts. The Smith remained in service but was eventually phased out.

Postwar Disposal and Surplus Sales

In June 1865, the Ordnance Department authorized soldiers to purchase their issued weapons:

- Muskets: $6

- Spencer Rifles: $10

- Other carbines/revolvers (including Smith): $8

Francis Bannerman & Sons later acquired thousands of surplus arms, listing Smith Carbines in their 1903 catalog for $2.75 each—a fraction of the price for Sharps or Spencers. Many were exported to Argentina for use in the War of the Triple Alliance, and to Irish-American Fenians for their 1866 invasion of Canada.

Shooting the Smith Today

Modern blackpowder enthusiasts can shoot Smith carbines using reproduction cartridges:

- Plastic Cartridges: Hold 40 grains of FFg powder. Reliable and inexpensive. Require sealing over the touch hole (e.g., cigarette paper).

- Brass Cartridges: Typically hold 24 grains. Easy to reload but offer reduced performance.

- Foil Cartridges (Reproduction): Offer historically accurate loads (50 grains, .512" bullet). Deliver best authenticity and ballistics.

Chronograph testing with Eras Gone .518" 354-grain bullets and Swiss 2Fg powder:

| Cartridge Type | Powder Charge | Muzzle Velocity | Energy (Joules) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foil (Crispin) | 50 gr | 283 m/s | 919 J |

| Plastic | 40 gr | 274 m/s | 861 J |

| Brass | 24 gr | 214 m/s | 525 J |

Conclusion

The Smith Carbine stands as a pivotal innovation in American firearms history. It bridged the gap between the unreliable early percussion breechloaders and the metallic cartridge revolution that followed. With over 30,000 issued, pioneering cartridge designs, and a durable break-action mechanism suited for mounted troops, the Smith earned its place in the pantheon of Civil War arms.

Today, collectors, reenactors, and blackpowder shooters continue to explore its mechanics and replicate its original ammunition. The Smith is more than a weapon; it is a testament to mid-19th-century ingenuity, industrial resilience, and the relentless American drive to improve under the pressures of war.

Read more about these rifles here:

Forums discussing these rifles can be found here.

If you know of any forums or sites that should be referenced on this listing, please let us know here.