The American Civil War, fought from 1861 to 1865, witnessed a rapid evolution in military technology, particularly in the development and deployment of small arms. Among the more obscure yet technically weapons fielded during the conflict is the Gibbs Carbine. Produced in limited numbers and briefly adopted by Union cavalry units, the Gibbs Carbine occupies a unique niche in Civil War firearms history. This article offers a definitive and in-depth examination of the Gibbs Carbine, detailing its origin, design, performance, deployment, and legacy.

Origins and Development

The Gibbs Carbine was named after its primary inventor, Lucius H. Gibbs, a gunsmith and firearms innovator from Rochester, New York. Gibbs patented his carbine design in the early 1860s, a period when the United States was urgently seeking effective breech-loading carbines for its mounted forces. Breechloaders offered a significant tactical advantage over traditional muzzleloaders: they could be loaded and fired from a prone or mounted position, improving both the speed and safety of reloading under fire.

The carbine was manufactured at the Phoenix Armory in New York City, operated by William F. Brooks and William W. Marston. The U.S. government ordered 10,000 Gibbs carbines, but only about 1,052 were completed and delivered before the Phoenix Armory was burned during the New York Draft Riots in 1863.These limited numbers make the Gibbs Carbine a rare and highly collectible artifact today.

The Partnership of Lucius H. Gibbs and Edward G. Marston

The invention of the Gibbs Carbine was not the product of a lone innovator working in isolation, but rather a collaboration between two minds whose combined skills shaped one of the most mechanically distinctive cavalry arms of the Civil War period. While Lucius H. Gibbs has historically received top billing in the naming of the carbine, his co-inventor, Edward G. Marston, played a critical—if often under-recognized—role in its development.

The Patent and Its Implications

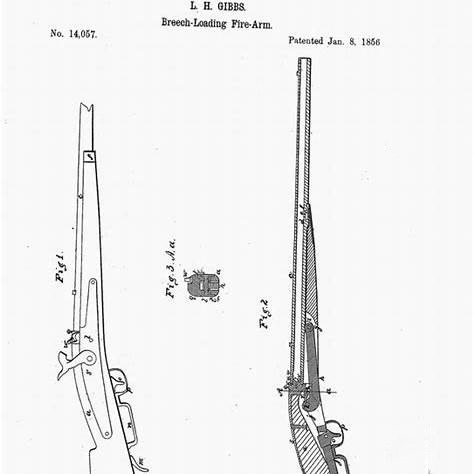

The Gibbs carbine design traces back to Lucius H. Gibbs’s mid-19th-century patents, including an 1847 patent for a repeating rifle and an 1856 patent that laid the groundwork for the single-shot carbine. The design allowed the shooter to operate a trigger guard-lever, which pivoted a breechblock downward to expose the chamber. This mechanism permitted rapid loading of a paper cartridge and was more mechanically sealed than many competing designs, minimizing gas escape at the breech—a common issue in other early breechloaders like the Burnside and the Cosmopolitan.

The patent included precise mechanical tolerances, emphasizing a snug fit between the breechblock and receiver to reduce fouling—a notable advantage in sustained use with black powder ammunition. The bolt’s operation was mechanically elegant and mechanically robust, a direct result of the synergy between Gibbs’ practical design instincts and Marston’s precise engineering background.

Who Was Edward G. Marston?

Edward G. Marston was a prolific firearms inventor and machinist operating out of New York in the 1850s and 1860s. Though overshadowed by more commercially prominent names, Marston held multiple patents across a variety of firearms platforms, including percussion ignition systems, breech mechanisms, and cartridge conversions. His work frequently involved mechanical solutions for more secure and efficient loading, firing, and reloading systems—concerns that became paramount as warfare transitioned from Napoleonic muzzleloaders to industrial-era breechloaders.

Marston’s prior work showed a strong preference for precision machining and modular construction, two features that became hallmarks of the Gibbs Carbine’s design. One of his earlier patents, U.S. Patent No. 33,597 (issued October 29, 1861), addressed improvements to percussion ignition systems—specifically designed to reduce misfires and increase weather resistance. These design priorities were echoed in the Gibbs/Marston collaboration, particularly in the carbine’s tight mechanical lockup and corrosion-resistant sealed breech area.

His background is not well documented in surviving archives, but census and city directory records suggest that Marston worked in the Rochester-Buffalo corridor, which was home to a growing cluster of machinists, toolmakers, and firearms developers. This industrial environment likely brought Marston and Gibbs into proximity and ultimately into partnership.

Contributions to American Arms Development

Marston’s influence extended beyond the Gibbs Carbine. He was among the class of lesser-known but highly influential mid-19th century firearms engineers who bridged the gap between hand-fitted artisan guns and factory-produced military arms. Alongside innovators like James H. Merrill, Sylvester Roper, and Jacob Snider, Marston contributed to a formative era of arms innovation characterized by rapid iteration, patent races, and private contracting with the War Department.

His work on the Gibbs Carbine illustrates several key themes of the period:

- Mechanization over craftsmanship: The design was built to tight tolerances and intended for repeatable production, reflecting the rise of interchangeable parts.

- Combat practicality: The mechanism was simple enough for soldiers to understand, maintain, and use under duress.

- Emphasis on sealing: His contributions to the breech design helped reduce fouling and gas leakage, crucial in an era when black powder fouling could cripple a weapon mid-battle.

Despite the carbine’s limited adoption, Marston's engineering fingerprints can be seen in later arms innovations, particularly in the development of post-war sporting rifles and the experimental carbines tested during the Indian Wars.

Historical Reassessment

Modern scholarship has begun to recognize the role of “supporting” inventors like Marston. While his name may not appear on the gun itself—most surviving examples are marked with “Gibbs Carbine” and serial numbers—Marston’s contribution is immortalized in the official patent record and in the functionality of every carbine that emerged from the Williamson & Co. factory.

Collectors and historians today are increasingly noting the dual-authorship of the carbine and emphasizing the mechanical elegance that distinguishes it from more crudely manufactured wartime arms. Including Marston in the story of the Gibbs Carbine not only corrects the historical record but deepens the narrative around the weapon’s invention and the minds behind it.

Technical Specifications

The Gibbs Carbine was a .52 caliber single-shot breech-loading rifle, designed primarily for cavalry use. Here are its key technical specifications:

- Caliber: .52

- Barrel Length: 22 inches

- Overall Length: Approximately 39 inches

- Weight: Around 7.5 pounds

- Action: Falling block breech-loading

- Stock: Walnut

- Sights: Iron front and adjustable rear sights

- Finish: Blued barrel and case-hardened receiver

The Gibbs Carbine operated on a falling-block mechanism that allowed a cartridge to be inserted directly into the breech when the breechblock was lowered. This design was innovative for its time and offered a quicker rate of fire than muzzle-loading counterparts.

The carbine was intended to use paper cartridges, a common ammunition format during the Civil War that combined a bullet and powder charge in a combustible or partially combustible paper wrapper. Soldiers would tear the cartridge, pour the powder into the breech, insert the bullet, and close the breechblock before cocking and firing.

Mechanical Design and Innovation

Lucius H. Gibbs' design stood out for its mechanical ingenuity. The carbine utilized a simple lever mechanism connected to the trigger guard, which the shooter would pull downward to lower the breechblock. This allowed the soldier to open the breech, insert a cartridge, and then close it with a swift upward motion. The lock was a conventional percussion system, fired by a hammer striking a percussion cap seated on a nipple located at the rear of the chamber.

The weapon featured a rear sight with multiple leaf elevations, allowing for engagement at various ranges. While not as widely refined as later repeating rifles, the Gibbs Carbine represented a significant step forward in battlefield ergonomics and rapidity of fire.

One of the carbine’s distinguishing features was its robust and clean design. The mechanism, while mechanically complex, was well-sealed and relatively protected from fouling—a major issue with black powder arms. Its wooden stock was well-shaped for horseback firing, and its metal parts were engineered to tight tolerances, reflecting high manufacturing standards.

Military Adoption and Use

The Union Army, particularly its cavalry, experimented with a wide variety of carbines during the Civil War. The necessity of arming thousands of mounted troops led to the adoption of numerous designs, many of which were procured in limited numbers for field testing.

The Gibbs Carbine was accepted for service following trials conducted by the Ordnance Department. A contract was issued for 1,052 units, which were delivered and distributed to several Union cavalry regiments, including the 10th New York Cavalry and potentially others engaged in operations in the Eastern Theater.

Field reports were mixed but generally positive. Soldiers appreciated the ease of loading and the carbine's relative reliability under combat conditions. However, by the time it entered service in 1863–1864, the market was already dominated by more prolific and logistically supported weapons like the Sharps Carbine, the Burnside Carbine, and eventually, the Spencer Repeating Carbine, which offered a seven-shot magazine fed by a metallic rimfire cartridge.

As a result, the Gibbs Carbine saw only limited deployment before the war ended in 1865, and it was never produced in sufficient quantities to make a major tactical impact. Nevertheless, its design was a proof of concept for breech-loading efficiency in cavalry firearms.

Comparison With Contemporary Carbines

In evaluating the Gibbs Carbine, it is essential to compare it with its contemporaries:

Sharps Carbine

- Caliber: .52

- Loading: Breech-loading with paper cartridges

- Action: Falling block

- Widely used with tens of thousands issued

- Known for durability and accuracy

Burnside Carbine

- Caliber: .54

- Used a unique brass cartridge

- Also had a falling block mechanism

- Saw significant service, though with ammunition supply complications

Spencer Carbine

- Caliber: .56-56 Spencer rimfire

- Seven-round tubular magazine

- Lever-action, repeating rifle

- Revolutionary firepower advantage

Compared to these, the Gibbs Carbine was mechanically reliable and accurate but lacked the production numbers and logistical support to become a widespread favorite. It was also a single-shot weapon, which by 1864 made it increasingly obsolete compared to repeaters like the Spencer.

Post-War Fate and Collectibility

After the Civil War, many surplus carbines were sold at auction or stored. The Gibbs Carbine, being rare even during the war, became almost nonexistent in subsequent U.S. military inventories. Its limited numbers ensured it did not appear in post-war conflicts, unlike the Sharps and Spencer models, which continued to see use in the Indian Wars and other frontier engagements.

Today, the Gibbs Carbine is a highly valued collectible, both because of its scarcity and its innovative design. Collectors prize specimens in good condition, especially those with matching serial numbers, intact markings, and original finish. Prices vary widely depending on condition, provenance, and completeness, with authentic specimens often commanding several thousand dollars at auction.

Markings on the carbine typically include the manufacturer's name and patent date, along with a serial number. Some examples also bear inspector’s cartouches, which further authenticate their military use and add to their historical value.

Legacy and Historical Significance

While the Gibbs Carbine did not achieve the fame or widespread adoption of its contemporaries, it remains an important artifact for several reasons:

- Engineering Milestone: Its breech-loading falling-block mechanism was a precursor to later developments in single-shot and repeating firearms.

- Innovation in Design: Gibbs’ approach to simplifying the loading process and enhancing battlefield usability was aligned with the tactical needs of the evolving Civil War battlefield.

- Historical Rarity: Its limited production run ensures that each surviving unit is a valuable physical link to the Union cavalry's efforts to modernize during one of the most technologically transformative conflicts in American history.

- Collector’s Interest: Among arms collectors and historians, the Gibbs Carbine holds a place of fascination not just for its rarity, but for the quality of its design and manufacture.

Conclusion

The Gibbs Carbine represents the ingenuity and industrial fervor of the American Civil War era. Though it did not become a standard-issue weapon, its thoughtful design and respectable battlefield performance placed it among the notable experiments in mid-19th-century military firearms. For historians, collectors, and enthusiasts of Civil War weaponry, the Gibbs Carbine offers a unique study in innovation, ambition, and the complex arms procurement processes of wartime America.

Its story enriches our understanding of the technological race that defined the Civil War and illustrates how even lesser-known firearms contributed to the broader evolution of modern small arms. As such, the Gibbs Carbine remains not just a rare collectible, but a crucial chapter in the narrative of American military history.

Read more here: For a broader look at how it fit among its contemporaries, see our overview of Civil War breech-loading carbines.

If you know of any forums or sites that should be referenced on this listing, please let us know here.

If you know of any forums or sites that should be referenced on this listing, please let us know here.