In the crucible of 19th-century warfare, one innovation changed everything—not a new kind of cannon, nor a radical new rifle, but a deceptively simple piece of lead with a hollow base. The Minié ball, named for French Army Captain Claude-Étienne Minié, turned the rifled musket from a specialist’s tool into the dominant infantry weapon of its era. Its emergence reshaped battlefield tactics, escalated the human cost of war, and laid the groundwork for the modern era of ballistics and small arms design.

Origins: Who Invented the Minié Ball?

The Minié ball was not a single moment’s invention, but the culmination of years of experimentation by European military engineers seeking to solve a critical problem: how to make rifled firearms as easy to load as smoothbore muskets.

In the 1830s, French officer Henri-Gustave Delvigne first proposed a conical projectile that could expand inside a rifled barrel. His design included a lead bullet that deformed under the force of ramming to engage the rifling grooves. However, it was inefficient, required considerable force to load, and lacked consistency in flight.

In 1849, Claude-Étienne Minié refined this concept with a breakthrough: a cylindro-conoidal bullet with a hollow base and an iron cup inserted inside. Upon ignition, expanding gases drove the cup into the cavity, forcing the soft lead sides outward to engage the rifling. This gave the bullet spin-stabilization and improved both accuracy and range, while remaining easy to load—even into a fouled barrel.

Minié’s innovation was adopted by the French military and soon caught the attention of other nations. The British adapted it for their Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle, and the Americans incorporated it into the Springfield Model 1855 and later the Model 1861, which would become the most common infantry weapon of the Civil War.

Before the Minié Ball: The Smoothbore and Early Rifles

For most of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the dominant infantry arm was the smoothbore musket, typically in .69 to .75 caliber. These weapons fired round balls that bounced down the barrel with minimal accuracy. Effective range was limited to under 100 yards, and often as little as 50 yards under field conditions.

Rifled muskets, with spiral grooves in the barrel to spin and stabilize a projectile, did exist. They were vastly more accurate, but loading them required hammering a tight-fitting bullet down the bore—impractical for combat. As a result, rifles were issued primarily to skirmishers and specialized marksmen.

The Minié ball bridged this gap. Its slightly undersized diameter allowed for quick loading, but once fired, it expanded to engage the rifling. For the first time in military history, the accuracy of rifles could be delivered at the speed of musket fire.

Design and Function: What Made the Minié Ball Revolutionary?

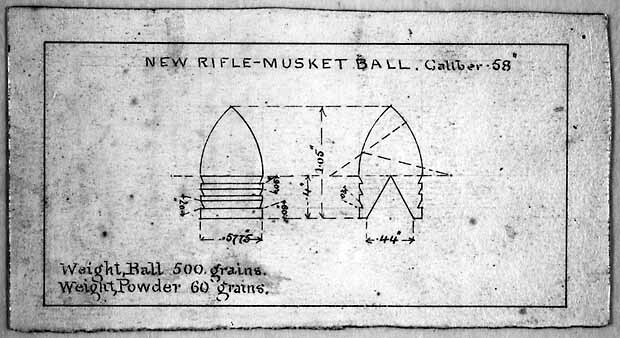

The Minié ball was a soft lead projectile, generally conical in shape with three or four exterior grease-filled grooves to hold lubricant and reduce fouling. Its defining feature was the deep hollow base, often containing an iron cup in early models. Upon firing, expanding gas forced the base to flare outward, pressing the bullet into the rifling grooves.

Key characteristics:

- Calibers ranged from .54 to .69, with .577 and .58 being the most common in British and American use respectively.

- Weight averaged 400–500 grains, depending on caliber.

- Paper cartridges held both bullet and powder, allowing soldiers to tear open the package, pour powder, and load bullet and wadding with speed.

This design gave soldiers:

- Fast reload times, similar to smoothbores.

- Dramatically improved accuracy, extending practical combat range to 200–300 yards.

- Increased muzzle energy, making wounds more devastating than previous musket balls.

Advantages of the Minié Ball

1. Combining Speed with Accuracy

Troops could now fire accurately at ranges up to 300 yards, while still reloading rapidly. The combination of ease-of-use and spin-stabilization was revolutionary.

2. Compatibility with Mass Rifled Musket Adoption

The Minié ball made rifling viable for general infantry arms. Soldiers could carry rifled weapons without sacrificing rate of fire. This led to nearly all major powers issuing rifled muskets by the 1850s.

3. Improved Manufacturing and Scalability

The bullets were easy to cast from soft lead and could be produced at scale in military arsenals. Paper cartridges with Minié balls became standard issue across European and American armies.

4. Lethal Terminal Ballistics

Upon impact, the soft lead bullet deformed, shattered bones, and caused massive internal trauma. The bullet’s mass and low velocity often caused it to yaw or change direction once inside tissue, leading to grievous wounds and high lethality.

Disadvantages and Human Cost

1. Devastating Wounds

The Minié ball inflicted catastrophic injuries. The large caliber, soft lead, and deforming nature made it vastly more destructive than earlier round balls. Bones were shattered beyond repair; soft tissue was often torn to pieces.

Surgeons, overwhelmed and under-equipped, resorted to amputation as the primary treatment for limb wounds. According to the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, over 60,000 amputations were performed by Union surgeons alone. Survival rates for major limb amputations hovered around 75%, but many soldiers succumbed to sepsis, gangrene, or tetanus within days.

2. Tactical Obsolescence

While the weapon changed, battlefield tactics didn’t. Generals, trained in Napoleonic linear tactics, ordered frontal assaults against entrenched positions defended by riflemen armed with Minié bullets. The result was slaughter on an unprecedented scale.

3. Slow Evolution in Command Culture

Despite the rifle-musket's effective range, many officers still trained troops for massed volley fire at short ranges. The full potential of the Minié was often unrealized in field usage, especially in the early stages of its deployment.

The Minié Ball in the American Civil War: A Weapon of Unparalleled Consequence

At the outbreak of the Civil War, both the Union and Confederacy quickly moved to standardize the rifled musket firing Minié-type projectiles. This shift turned the average infantryman into a long-range killer—and the battlefield into an unprecedented meat grinder.

Weapons of the Conflict

- Springfield Model 1861 (.58 caliber): The standard Union rifle-musket, produced in huge quantities. Accurate and robust.

- Pattern 1853 Enfield (.577 caliber): Imported in vast numbers, especially by the Confederacy, and functionally equivalent to the Springfield.

These rifles, paired with Minié bullets, delivered shocking accuracy, killing power, and consistency. Yet military leaders failed to adapt their tactics accordingly.

Battlefield Consequences

In set-piece battles, the Minié ball dictated outcomes.

- At Fredericksburg, Union troops charged up Marye’s Heights into Confederate rifled musket fire. The result: over 12,000 Union casualties in a single day.

- At Gettysburg, Pickett’s Charge faced entrenched Union lines with rifles ready. Confederate casualties were staggering before they ever closed to within 100 yards.

- At Antietam, the Minié ball turned the Cornfield, Bloody Lane, and Burnside’s Bridge into charnel houses—23,000 men fell in just twelve hours.

The new weapons demanded cover, concealment, and entrenchment—but tactics were still rooted in massed ranks and close-range assaults. The result was catastrophic loss of life.

Medical and Cultural Impact

The Minié ball’s horrific wounds overwhelmed Civil War field hospitals. Compound fractures from bone-shattering bullets left no choice but amputation. Soldiers feared the surgeon’s knife as much as enemy fire. Hospitals became factories of dismemberment.

The psychological trauma was just as significant. Soldiers feared being shot more than they feared close combat, as the Minié ball offered death or mutilation from distances once thought safe.

Wounded veterans returned home in vast numbers. The war birthed the modern American system of prosthetics, military pensions, and long-term veteran care. The cause? A bullet small enough to fit in your palm.

The End of the Minié Era: Breechloaders and Metallic Cartridges

By the late 1860s, the age of the muzzle-loading rifle-musket was ending. Breech-loading rifles—like the Sharps, Snider-Enfield, and Springfield Model 1866 “trapdoor”—used metallic cartridges that were faster, more reliable, and cleaner. The bulky Minié-style bullet was replaced by smaller-caliber, elongated, jacketed bullets designed for higher-velocity rifled weapons.

The development of smokeless powder in the 1880s and the adoption of spitzer (pointed) bullets further pushed bullet design into the modern age. Still, the principles Minié helped normalize—spin-stabilized projectiles, bullet-to-bore obturation, mass-production compatibility—endured.

Legacy: The Minié Ball’s Enduring Impact

The Minié ball was more than just a bullet. It catalyzed the full-scale adoption of rifled infantry weapons, shattered outdated tactical doctrines, and transformed the physical and psychological experience of war.

- Military doctrine began to emphasize entrenchment, dispersed formations, and aimed fire.

- Medicine advanced rapidly under duress—military hospitals developed triage systems, better amputation techniques, and eventually antiseptic procedures.

- Ballistics science embraced spin stabilization, bullet aerodynamics, and material science innovations.

It also marked a turning point in the relationship between man and war. No longer did massed formations decide battles at bayonet point. Now, a man behind cover, armed with a Minié bullet and a rifled musket, could kill at several hundred yards—and often did.

Conclusion

The Minié ball marks a turning point in the history of warfare—deceptively simple in form, yet devastating in function and effect. By solving the ancient dilemma of rapid rifled fire, it elevated the common infantryman’s power, increased the range and lethality of battlefield engagements, and hastened the demise of traditional 18th-century tactics.

It ushered in new horrors of war, forced military and medical revolutions, and left a trail of amputated limbs, shattered bones, and altered doctrines across Europe and America. Though its era was brief, its impact was immense. Behind its soft lead, there lies a hard truth: war would never again be the same.

Shoop, Isaac. “Small but Deadly: The Minié Ball.” The Gettysburg Compiler, April 27, 2019. https://gettysburgcompiler.org/2019/04/30/small-but-deadly-the-minie-ball/.

Leonard, Pat. “The Bullet That Changed History.” The New York Times. The New York Times, September 1, 2012. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/31/the-bullet-that-changed-history/

If you know of any forums or sites that should be referenced on this listing, please let us know here.