Introduction: A Turning Point in Cavalry Warfare

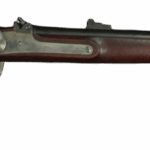

Among the many innovations of the American Civil War, few small arms defined the shifting tides of military technology like the Burnside Carbine. Developed in the shadow of looming national conflict and issued extensively to Union cavalry, this .54 caliber breechloading firearm represented a fundamental departure from the slow, cumbersome muzzle-loaders that had dominated battlefields for centuries. With its distinctive brass cartridge and refined breech mechanism, the Burnside offered enhanced reload speed, greater reliability, and tactical advantages that revolutionized mounted combat.

More than 55,000 of these carbines were produced during the war, making the Burnside Carbine one of the most widely deployed breechloaders of the era. Though ultimately overshadowed by repeating arms like the Spencer and Henry rifles, the Burnside Carbine remains a keystone in the evolution of American military firearms—bridging the gap between blackpowder muzzleloaders and the era of metallic-cartridge repeaters.

Origins and Invention: Ambrose Burnside’s Vision

The Burnside Carbine was developed in the mid-1850s, when its inventor, Ambrose Everett Burnside—an 1847 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point—applied for U.S. Patent No. 14,491 for a breech-loading carbine that used a self-contained brass cartridge. The patent was granted on March 25, 1856. At a time when most military arms still relied on loading powder and ball down the barrel, Burnside’s design offered a radical alternative.

Burnside's concept was aimed squarely at improving the cavalryman's effectiveness. Mounted troops needed speed, mobility, and the ability to reload without dismounting—needs ill-served by traditional muzzle-loaders. The Burnside carbine utilized a hinged breechblock and a uniquely tapered brass cartridge that formed an effective gas seal when fired, minimizing blowback and fouling.

A second patent in 1856 (U.S. Patent No. 15,275) further refined the design. Burnside improved the sealing surfaces and lockwork, increasing both safety and mechanical reliability. These innovations earned the attention of military planners, even if commercial success initially eluded him.

Manufacturing History: Bankruptcy, War, and Mass Production

Despite the elegance of his design, Burnside’s early attempts to commercialize the carbine through the Bristol Firearms Company of Rhode Island were unsuccessful. Financial struggles led to bankruptcy in 1857, forcing Burnside out of the arms business temporarily. Ironically, his financial failure freed him to pursue a political and military career—one that would later see him command Union forces and become a household name in both military and facial hair history.

Yet Burnside’s rifle would not die with his business. The patent rights were acquired and revived by the newly organized Burnside Rifle Company of Providence, Rhode Island. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the Union government, desperate for reliable breechloaders, began placing substantial orders. Over the course of the war, more than 55,500 Burnside Carbines were produced under government contract.

To meet rising demand, subcontractors including the Massachusetts Arms Company and the National Arms Company were engaged to boost output. All told, the Burnside Carbine became one of the principal cavalry carbines of the Union Army, surpassed only by the Spencer and Sharps in overall prominence and tactical effect.

Design and Operation: Breechloading with Brass Precision

The Burnside Carbine was a single-shot, percussion-fired, breechloading carbine chambered in .54 caliber. Its defining feature was the use of a unique, proprietary brass cartridge shaped like an elongated teardrop or acorn, with a flared base and tapered body. The cartridge contained a conical lead bullet weighing approximately 380 grains, backed by 46 grains of black powder.

To load the Burnside, the shooter first released a locking latch and pivoted the breechblock downward, exposing the chamber. The cartridge was inserted base-first, and upon closing the breech, a tight gas seal was created. A percussion cap placed on the external nipple would ignite the powder charge upon hammer fall, propelling the bullet down the 21-inch rifled barrel at approximately 900 feet per second.

The brass cartridge was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it offered better sealing than paper or linen cartridges, dramatically reducing gas loss and barrel fouling. On the other, the proprietary nature of the ammunition limited interchangeability and sometimes caused extraction issues when spent cartridges expanded in the breech.

Combat Effectiveness and Field Use

The Burnside Carbine was a preferred weapon among Union cavalry units due to its ease of use, reliability, and faster reloading speed compared to muzzle-loaders like the Springfield Model 1861. Soldiers equipped with Burnside Carbines could fire significantly more rounds per minute than those using traditional rifled muskets.

Union cavalry units prized the Burnside Carbine for its mechanical simplicity, robust construction, and quick reload capability. It saw widespread deployment across major theaters of war from 1861 onward. Troopers of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, 1st Maine Cavalry, and 3rd Indiana Cavalry, among others, used it in important battles including Antietam, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga.

Compared to the Springfield Model 1861 rifled musket, the Burnside offered a dramatic improvement in fire rate. A skilled soldier could fire 5 to 7 shots per minute with the Burnside, more than double the rate achievable with a muzzleloader. In the dynamic, close-range engagements common to cavalry operations, this offered a distinct tactical edge.

However, it was not without flaws. One persistent complaint was the difficulty of extracting spent cartridges, particularly after rapid fire caused brass expansion in the breech. Some soldiers carried a short rod or improvised tool to aid in removal. Nevertheless, the Burnside remained favored for its ruggedness, especially in comparison to more delicate or experimental designs issued in limited numbers.

Technical Specifications

- Caliber: .54 Burnside (proprietary tapered brass cartridge)

- Barrel Length: 21 inches

- Overall Length: Approximately 39 inches

- Weight: About 7.5 pounds

- Action: Single-shot, percussion-fired, breechloading

- Ammunition: 380-grain lead bullet, 46 grains of black powder

- Muzzle Velocity: ~900 feet per second

- Sights: Folding leaf rear sight, fixed front post

The tapered design of the cartridge allowed for easier insertion and ensured a better seal, reducing the amount of escaping gas and increasing efficiency. However, despite its advantages, the Burnside's ammunition was proprietary and not interchangeable with other carbines, which sometimes caused logistical challenges in resupplying troops in the field.

Comparison to Civil War Carbines

The Burnside Carbine was not alone in the race for a better battlefield arm. As the war progressed, other breechloaders and early repeaters emerged, including:

- Spencer Repeating Carbine: Featuring a 7-round tubular magazine and lever-action mechanism, the Spencer delivered exceptional sustained fire for the time. Chambered in .56-56 Spencer rimfire, it was faster and easier to reload, but also more complex and expensive to produce.

- Sharps Carbine: A single-shot design using linen or paper cartridges, the Sharps was known for its rugged reliability and exceptional accuracy. Its falling-block action was simple, durable, and popular among sharpshooters and cavalry alike.

- Gallager Carbine: Another .52 caliber percussion carbine with a metallic cartridge system. While innovative, the Gallager suffered from gas leakage and breakage under sustained use, issues the Burnside mitigated with better sealing.

While repeaters like the Spencer ultimately stole the spotlight, the Burnside held its own through the mid-war years and remained in use until war’s end. Its balance of innovation, durability, and moderate cost made it a workhorse for thousands of cavalrymen.

Postwar Decline and Historical Legacy

With the war’s conclusion in 1865, the Burnside Rifle Company—its wartime contracts completed—soon ceased operations. The rise of metallic-cartridge repeaters like the Winchester and Remington Rolling Block signaled the end for percussion-fired single-shots. Many surplus Burnside Carbines were sold to state militias or civilian buyers in the years after the war but were quickly eclipsed by newer repeating arms.

Yet the Burnside's legacy remains secure. It was among the first U.S. military firearms to successfully combine a breechloading design with a self-contained metallic cartridge. Its innovations helped pave the way for the cartridge arms revolution that would dominate the latter half of the 19th century.

Collectors today value the Burnside for its unique place in firearms evolution and for its historical significance. Variants with original serial numbers and regimental markings—particularly those linked to known cavalry regiments—command high interest in Civil War firearms circles.

Conclusion: The Burnside’s Enduring Influence

The Burnside Carbine is a symbol of transitional warfare—a weapon that bridged the blackpowder past with the metallic future. Though ultimately surpassed by lever-action repeaters and bolt-action rifles, it played a decisive role in modernizing the cavalry arm of the Union Army during the Civil War. Its robust engineering, innovative ammunition, and field reliability helped rewrite the tactical playbook for mounted troops.

As both a collectible artifact and a technological milestone, the Burnside Carbine remains a centerpiece in any discussion of Civil War firearms. Its story is not merely one of design and manufacture—it is a tale of adaptation, innovation, and the inexorable march of military progress.

Read more here:

The Muzzleloading Forum has some threads on the Burnside Rifle.

The Burnside Carbine is one of many Civil War arms worth knowing. Browse more in our history section.

If you know of any forums or sites that should be referenced on this listing, please let us know here.